The Babraham Institute as it exists today was established in 1993 to study the biological mechanisms underpinning human biology, health and ageing. Research on the Babraham estate actually dates back to the Institute of Animal Physiology established in 1948 to help the nation recover following the Second World War.

Before the Institute (pre-1948)

The name Babraham probably originates from the Anglo Saxon period (1000 to 1600 years ago), meaning the home of Barbara ("Badburgh"), thought to be the daughter of a local Chief. Yet historical evidence shows that people lived in and around Babraham as far back as the Mesolithic period (5000 to 15000 years ago).

Much of the land around Babraham eventually came to be owned by the Church before being taken over by King Henry VIII in 1539. The land passed through several owners until 1576 when Robert Taylor built the first great house on the Babraham estate. The construction of the hall and its gardens involved the demolition and re-siting of Babraham village to its present location.

The first house was demolished in 1768 by Robert Jones, Director of the East India Company, and a much simpler country house was constructed in its place. The modern Babraham Hall that forms part of the Babraham Research Campus is the third great house on the site and was built by Jones’ son Henry John Adeane (pictured right) between 1832 and 1837. The house was designed in the Jacobean style by Philip Hardwick. The Adeanes held the land through until the mid-20th century although it was leased to various tenants.

Download our History of Babraham and Babraham Archaeology booklets to discover more about our history prior to World War II.

The Institute of Animal Physiology (1948 to 1993)

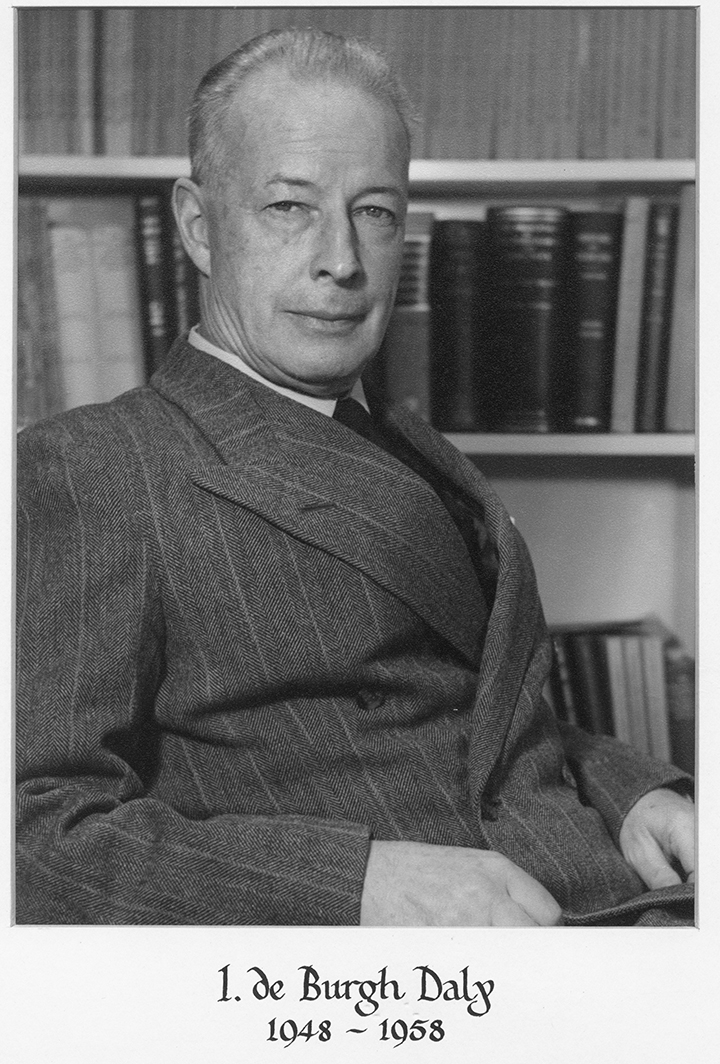

In the wake of World War II, Britain recognised the need for research into more sustainable and independent agricultural practices to help the nation recover and to be better prepared for any future hardships. In 1948 the Babraham estate was purchased from the Adeanes by the Agricultural Research Council to create the national Institute of Animal Physiology (IAP) with Professor Ivan De Burgh Daly FRS (pictured left) as its founding Director.

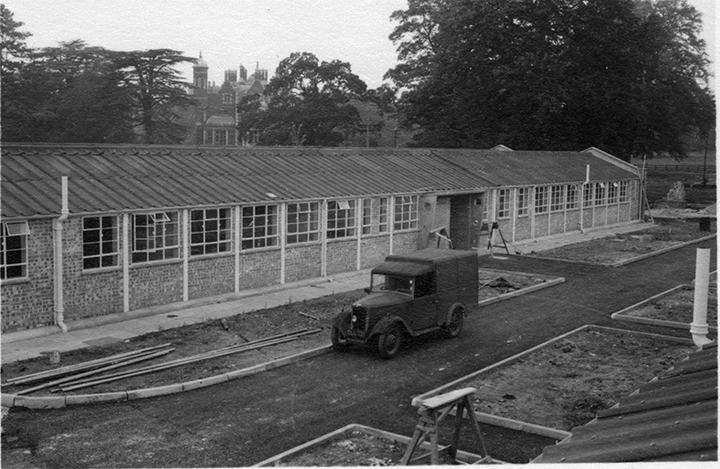

The new Institute saw extensive changes inside the Hall. The breakfast room became one of the first laboratories and an operating theatre. The drawing room became laboratory stores, and workshops and darkrooms were installed in the basement. This period also saw the construction of various lab huts on the site (shown below) as well as the creation of our on-site accommodation as a way to support researchers relocating into the area.

A decade after founding the IAP, Professor Daly stepped down as Director, passing responsibility to Sir John Henry Gaddum FRS, a renowned pharmacologist known for studying the effects of drugs on nerve communications. In 1964 the mantle then passed to Richard Darwin Keynes CBE FRS, a physiologist and great-grandson of Charles Darwin.

Alec Bangham FRS joined the Institute in 1952. In 1965 he produced early evidence to suggest cell membranes are made of double layers of lipid molecules. He also discovered ‘Banghasomes’ simplified lipid structures now known as liposomes. Liposomes helped scientists to examine the structure and organisation of cells and have since been investigated as a way to target drugs and other substances for targeted delivery to specific cells.

Sir Barry Cross FRS, physiologist, took over the Institute’s Directorship in 1974. He would become the Institute’s longest serving Director, holding the role until 1989.

In 1977 a collaboration between Geoff Butcher and Jon Howard with César Milstein (Nobel Prize, Pysiology & Medicine 1984) at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB), led to the first ‘useful’ monoclonal antibodies. This work has allowed scientists to use antibodies to track cells and proteins in their studies and has resulted in several monoclonal antibody drugs such as Herceptin and infliximab.

Work published by Professor Azim Surani FRS (shown left) in 1984 revealed the discovery of mammalian genomic imprinting. Although we have two copies of most genes, one from each parent, imprinting means that, for some genes, we rely more on one copy than the other. This provided a crucial fundamental insight into genetics and development. Professor Wolf Reik FRS (then a postdoctoral researcher) would later work alongside Surani to show that imprinting is driven by an epigenetic system of DNA methylation. Reik still leads a group at the Institute today.

In 1986, the IAP joined with two organisations based in Roslin, Scotland to form the Institute of Animal Physiology & Genetics Research (IAPGR) with funding from the Agricultural & Food Research Council (AFRC). During this time, the IAPGR worked on developing the cloning techniques that would eventually produce Dolly the Sheep at Roslin in 1996.

1989 saw Sir Robert Brian Heap FRS become the new Director. Heap was a specialist in studying the role of hormones in animal reproduction. He would oversee the final years of the IAPGR and the creation of the Babraham Institute.

The Babraham Institute (1993 onwards)

The early 1990s saw shifts in national research priorities and the Institute became the responsibility of the Biotechnology & Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) formed from the AFRC. In 1993, the Babraham Institute (1993 staff picture shown left) was created from the Cambridge-based part of the IAPGR, while the Scottish part became the Roslin Institute, now part of the University of Edinburgh. Over the next five years, agricultural research was phased out and our major focus shifted to understanding the biology underpinning human development, health and ageing.

The monoclonal antibody techniques we developed with the MRC-LMB in the 70s were licensed for commercial development in 1993. The work was taken forward by Abgenix, who were bought for $2.2bn by Amgen 15 years later. Abgenix developed panitumumab (Vectibix) which is now used to treat certain bowel cancers.

Richard Dyer (shown left) took the lead of the Institute from Brian Heap in 1994. Dyer specialised in understanding how nerves regulate hormone release. Dyer’s vision was of an integrated Babraham Research Campus that would unite academics and commercial research scientists in one place to give more rapid development of new discoveries into impacts and applications.

1994 saw the Institute host its first annual Schools' Day. Each year we open our doors to secondary school and sixth form students for a day so that they can come into our labs and find out more about what it's like to pursue a career in research, while also learning more about the latest science. Schools' Day is still part of the Institute calendar today.

In 1996, the Institute created the company Babraham Bioscience Technologies Ltd. with responsibility for developing the Babraham Research Campus. Their goal was to find small-scale organisations with complementary interests to the Institute and enable them to come and work alongside us on the Campus. Initially new companies worked in existing laboratories alongside the Institute (shown; the Campus as it appeared in 1998). The company changed its name to Babraham Research Campus Ltd. in 2021.

By 1998, all research involving large animals had ceased on the site. Current research at the Institute uses rodents (mainly mice) or alternative systems such as tissue culture, organoids and computer models.

Collaboration with the MRC-LMB in 1999 led to the first detailed structure of the lipid signalling protein PI3K gamma. This unlocked new possibilities for designing and developing drugs to control this protein and others like it. Since PI3K proteins are key in controlling cell growth and have been linked to various illnesses, these drugs could have widespread applications.

For a complete exploration of our work on PI3 kinases and their subsequent investigation as drug targets download our cell signalling timeline posters.

The 2000s

Research published in 2002 highlighted the importance of genomic imprinting mechanisms discovered in the 1980s. The work shows that imprinting affects how quickly babies grow before birth by changing how easily nutrients pass through the placenta from mother to baby.

In the same year, we developed a new method called ribosome display. The technique allowed better antibodies to be created that could more precisely find their correct targets. This further improved their potential for use as cell or protein trackers in research and as drugs in the clinic. The technology was later developed by a spin-out called Discerna and subsequently by Crescendo Biologics.

Also in 2002, we showed that genes can be regulated by genetic sequences that are a long way from the genes themselves. We now know that DNA inside cells can form loops bringing distant genetic sequences close together inside the cell and this can have a dramatic effect on the activity of many genes.

Between 2005 and 2012, the first custom Bioincubators – Minerva, Meditrina, Maia and Moneta (shown left) – were built on the south side of the Campus, providing new spaces for companies coming to the Campus. This period also saw the demolition of some of the original IAP buildings.

Between 2005 and 2007, Dr John Bicknell became acting Director until Professor Michael Wakelam took the reins. Director from 2007 until his untimely death in 2020, Wakelam was an expert in lipid biology and played a key role in the development of lipidomics research – simultaneously studying the roles of all lipids inside cells.

Crescendo Biologics Ltd. was founded as a spin-out from the Institute in 2008. Crescendo’s goal is to use antibody techniques that were developed here to develop better antibody-based anti-cancer therapies. In 2018 TaKeDa Pharmaceuticals agreed an exclusive license to further develop some of Crescendo's potential therapies.

Crescendo Biologics Ltd. was founded as a spin-out from the Institute in 2008. Crescendo’s goal is to use antibody techniques that were developed here to develop better antibody-based anti-cancer therapies. In 2018 TaKeDa Pharmaceuticals agreed an exclusive license to further develop some of Crescendo's potential therapies.

In 2009, the Institute opened the present Biological Support Unit (BSU) animal facility on the Campus, which has since been extended to add more capacity. The BSU is a specialist small-animal research facility and is a global flagship for animal welfare, animal technician training and staff wellbeing.

The 2010s

2010 saw the Institute working with the Department of Health to examine the effects of mobile phone radiation on health.

In 2011, we worked in partnership with the National Institute for Medical Research to reveal how green vegetables contribute to intestinal health by supporting cells in the immune system.

2014 was the year we became a founding signatory of the Concordat on Openness on Animal Research, this further consolidated our commitment to being open about our research using animals and working together with the public on the issues surrounding animal research. Our commitment to the Concordat has been recognised several times, including a commendation for providing visitors with virtual tours of our animal facility and an award for our work with schools on the practicalities and ethics of research using animals.

Our epigenetic studies in 2013 demonstrated that epigenetic reprogramming plays a key role in the capacity of stem cells to produce a wide variety of different types of cells (pluripotency), a critical part of development. Understanding stem cells underpins the concept of regenerative medicine – a future type of medicine that could allow us to grow and replace whole body parts.

In 2013 we also revealed the first views of how DNA is arranged inside cells. These insights into chromosome architecture help us to understand how genes are regulated in different types of cells. In 2017, we worked with visual artist Andy Lomas and musician Max Cooper to create an immersive VR experience called CHROMOS based on this research.

With colleagues at the University of Cambridge, this was also the year that we discovered a new human genetic condition that is responsible for recurrent lung infections. APDS, or Activated PI3K Delta Syndrome, affects the immune system and increases the risk of infections. We’re now using our expertise with PI3K to find new treatments for this illness.

Further development of the Campus from 2013 to 2015 led to the Jonas Webb, Eddeva and Bennet buildings (shown right) on the north side of the campus. 2013 also saw the establishment of Babraham Commercialisation Services (now Babraham Institute Enterprise Ltd.) which facilitates the commercialisation of Institute research in partnership with companies.

In 2014 we joined the EU-LIFE network of 13 life science research institutes across Europe. The goal of EU-LIFE is to build collaborations, develop careers, share best practice and expertise while also representing the scientific community as an influential voice in European scientific policy. With EU-LIFE colleagues we have secured funding for LIBRA and ORION projects which respectively investigate ways to improve equality and openness in science.

Thanks to funding from the Global Challenges Research Fund, in 2016 we launched new work investigating the effects of ageing on health in developing countries, particularly looking at the effect of age on the immune system and the body’s capacity to protect itself from disease.

In 2017 a third round of Campus expansion was announced. Biomed Realty would provide two further buildings with flexible space and facilities to support larger companies.

Our research in 2017 leads to an epigenetic ageing clock that can be used to measure the rate of ageing in mice; the most precise way to track the ageing process. The eventual hope is that the epigenetic clock could help us to find ways to slow biological ageing. We also show that restricting the diet of mice can significantly extend their lifespans. This work formed the basis of the Race Against the Ageing Clock public exhibit launched at the Royal Society in 2018.

In 2018, we found a mechanism that gut bacteria can use to control some of our genes.

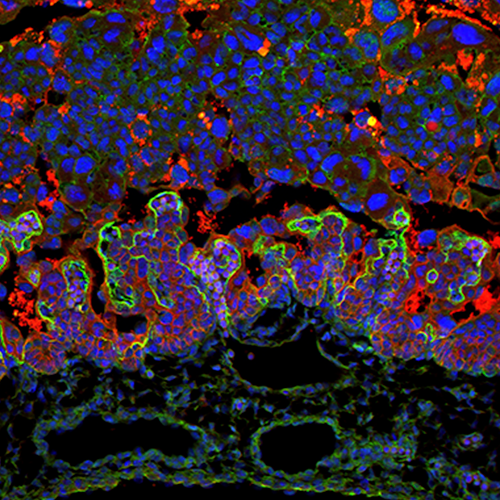

Our work as part of the Deciphering the Mechanisms of Developmental Disorder consortium led to one of the first systematic studies of gene effects in the placenta (placenta cells shown right) and showed that many more genes than expected could contribute to prenatal deaths. This research was led by Dr Myriam Hemberger (now at the University of Calgary) who went on be a winner of the inaugural Magee Prize for research into reporduction and women's health.

In September 2018, we worked together with other research organisations in Cambridge to launch LifeLab, a public celebration of European-funded research that formed part of the European Researchers Night that takes place each year across Europe.

This year's research also led to a possible new way to tackle the common cold, by targeting fatty molecules called lipids.

In 2019-2020 the Institute experienced an exciting phase of new growth. Our work on human health and ageing continued with our research focusing on three key areas: epigenetics, signalling and immunology. We recruited new group leaders to expand and enhance our scientific expertise and explore exciting new directions of inquiry, welcoming Dr Hayley Sharpe (August 2019 announcement) and Dr Rahul Samant (October 2019 announcement) to the Signalling programme to explore the biology of protein tyrosine phosphatases and protein folding respectively. Dr Maria Christophorou joined the Institute’s Epigenetics programme in January 2020 (announcement) to work on the mechanisms that modulate the function of epigenetic regulators.

Our research facilities also expanded their capacities and continued to provide vital services to the Institute and other local organisations. The Babraham Research Campus too continued to grow, now hosting around 60 commercial organisations with more to come following the completion of the Biomed@Babraham development. Michael Wakelam shared his thoughts on the importance of personal development and the importance of nurturing the individual to enable the best environment for the best research in a Vision piece for the FEBS Network (staff photo 2018 shown below). The Institute was also proud to become a signatory of the Technical Commitment, pledging to increase recognition and support for Institute’s community of technical specialists who contribute essential technical expertise in vital roles across the Institute.

To discover more about our current research, head over to our research pages and latest news and read more about the groups currently working at the Institute. Our annual research reports present a year-by-year look at our research from 2016 onward.To explore some selected highlights and research stories have a look through our research features, and for personal perspectives on life at the Institute, careers, public engagement, knowledge exchange, sustainability and equality, visit our blog.